SHARE

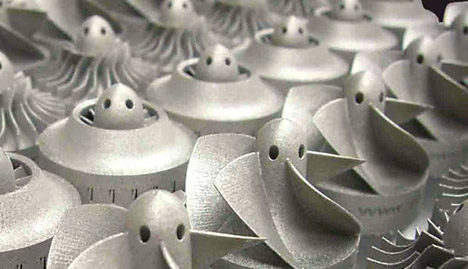

3D Printing Metal Parts: Lost-Wax Casting or DMLS?

Both metal alloy prototyping and small-series production have significantly progressed thanks to the 3D printing technology. However, there are some techniques that have not disappeared but evolved.

This is the case of ‘lost-wax casting’ manufacturing, a millenary technique that evolved from making a handcrafted part using wax, to making light molds for the wax to manufacture small series, to finally manufacturing a part in a kind of resin or PLA with a conventional 3D printer.

PLA, a cheap material used in almost every 3D printer, is used to manufacture an original part. This part is later introduced in the sand with a binding agent and heated up to form a mold.

A few years ago, when this technique was still not commonly used, ennomotive launched a contest to help a Hight Tech company find a faster and cheaper process to manufacture titanium parts for the aviation industry (both prototypes and small series). At that time, this company was using metal injection molding, which costs a lot of money and time.

One of the contest participants, an engineer from the Gaza, proposed the lost-wax casting manufacturing method as a solution. He had studied Engineering in the US and his final thesis covered this 3D printing technique, PLA and lost-wax casting manufacturing. He knew its benefits very well.

The company team could not believe that this solution could save months and thousands of euros since lost-wax casting had not been proposed internally before. They asked if the final part, manufactured through this process, complied with the industry specifications. They were able to confirm that there were manufacturers already providing such service with a 3-day lead time.

A few years ago, 3D printers could print metal parts with a few alloys and with a poor-quality superficial finish compared to parts made by injection molding. Today, metal 3D printed parts have significantly improved their technical properties, their cost has dropped, and the number of available alloys has increased.

Since DMLS technology has improved so much, what would be the result if we launched the same contest again? Some thoughts:

- The most likely answer would be ‘it depends’. It really does, it depends on the part to be manufactured, on the technical requirements, on the size, the materials, etc.

- Some engineers might recommend to modify the design or to change the material, as happened during the contest (they suggested to use some kind of resin instead of metals).

- Since the shape of the original part was not so complex and the material was a special alloy, we would probably pick lost-wax again for small series.

- Lost-wax casting manufacturing achieves better superficial finishes but DMLS comes second thanks to the additives it uses.

- Both have similar precision, although some authors consider that lost-wax is still better.

- Regarding size, lost-wax can be used to print out big parts (around 2m), while DMLS usually makes smaller ones that can be assembled to achieve the required size.

- Lost-wax allows the use of a broader range of materials than DMLS.

- DMLS can make more complex geometrical shapes (e.g. internal structures in a tetrahedron) and thinner walls. Lost-wax admits complex shapes but with limitations.

- DMLS can print two different assembly components at the same time.

- Regarding time and cost, lost-wax still performs better, which is why it is still being used in aviation. However, DMLS is progressing very fast in this sense (e.g. the new HP printers).